Gentrification, Rural Communities, and Detroit

Oh, look, it's another installment of 'different examples, same questions'.

One of the most useful tools I have for predicting what the economy is going to do is imagining it as a river.

A river is a powerful force that follows the most efficient path to get where it’s going. It does not care if it is cutting through land. It does not care if there is a town in its way. It follows the efficient path.

I like this image because water feels neutral. We don’t get caught up judging water for being like this. We accept it to be true and we respond accordingly.

The economy is also going to follow the most efficient path. That means it is going to follow the path that costs the least amount of money. We can accept this to be true and respond accordingly.

Sometimes we do not want a river to follow this efficient path. If so, we can put up barriers that make the river take a different route.

Sometimes we do not want the economy to follow the efficient path. If so, we can implement market interventions that make the economy operate differently.

Why would we not want the efficient path?

Sometimes the efficient path destroys a thing we care about.

Today’s post is about market interventions to save communities.

We talk about the economy shaping communities all the time. We say gentrification, the death of rural America, and the crisis in Detroit. We say rent control, tariffs, zoning laws, and jobs acts. I rarely see a political debate that does not feature these topics.

No one ever wants to frame their proposed solution to save a culture as a market intervention. Market intervention sounds bad. ‘Free market good, intervention bad.’ But we intervene all the time and talk about it even more.

The thing we tend to really ague over is when to intervene. Which communities are worth protecting and what prices we are willing to pay to do that?

Do you care about the housing crisis in Bozeman? The population collapse of Appalachia? What’s happening to Harlem?

In the next section I’m talking (writing?) us through examples. When I’m confronted with these topics, I use the following three prompts to make the question precise. So that’s the framework we’ll use.

How much destruction is economic efficiency causing?

Who is being affected?

Who would pay if we intervened and how much would it cost?

Oakland, California

Wealthier residents of San Francisco are moving into Oakland and displacing the existing population. The change is leading to a fundamental culture shift. "Between 2000 and 2014, Oakland saw an absolute loss of 43,777 Black residents — equivalent to 31 percent of its Black population.”

PBSHow much destruction is this?

This is why these questions are so tricky. The magnitude of the destruction depends on who you ask, and there is no way to calculate the amount of destruction without emotional judgements. The value is the value of a Black community in a country where that is rare.Who is being affected?

The lower income residents of Oakland. Individuals who value the existence of Oakland as it currently is, even if they do not live there.Who would pay if we intervened and how much would it cost?

This depends on the strategy used to keep the community preserved.We could make it illegal for new people to move in (this is unlikely).

The people who are not allowed to move there but would have benefitted from the move are paying, as are the businesses that would have made money from them.

We could implement rent control.

The house owners who would have made money from renting their properties at a higher rate. The tenants who will most likely have lower housing quality.

We could freeze property taxes so homeowners have an incentive to stay.

The community that would have benefitted from the use of the tax revenue.

We could make the community so unappealing to businesses and new residents that no one would want to move there.

The people in the community who will now live in a less appealing place.

We could ‘build affordable housing’.

The government (read: the people) who are subsidizing the lower cost housing.

Detroit, Michigan

Beginning in the 1950s, manufacturing jobs, particularly automobile, were outsourced to other countries. The result is an economy that collapsed and the resulting out-migration of people.How much destruction is this?

See above re: this being tricky to measure. As before, we are talking about a major change. It’s not a loss of the type of work that exists in this community, as in everyone having to switch from building cars to building boats, it’s people having to move away from their home to stay employed.Who is being affected?

Everyone in Detroit who worked in one of the manufacturing jobs that was outsourced, the family members who share money with them, the businesses that these workers were patrons of, and the city that was using their tax dollars.Who would pay if we intervened and how much would it cost?

The currently proposed solution is to implement tariffs. Tariffs raise the price on goods made in foreign countries. A tariff on automobiles would make people more likely to buy a car made in America, and this could bring automobile manufacturing back to Detroit. It’s the Uno Reverse card of outsourcing jobs overseas. The people who would pay for this are consumers who are now purchasing a car that costs more.

We could also invest in bringing jobs to Detroit that are not manufacturing related. This could solve the problem of the economy dying, but would leave the loss of the ‘manufacturing way of life’. The cost of this would be the cost of the government efforts to bring those industries to Detroit.

Downs, Kansas

Downs is one of many agricultural towns in the United States that is losing its population and economic vibrancy. This article is a compelling narrative of what that really means.How much destruction is this?

What is the value of rural life in America? Downs, Kansas is an example town, but it’s happening all over.Who is being affected?

The farmers of America and the small towns that exist to support them. This includes the teachers, doctors, and grocers that lived in those small places.Who would pay if we intervened and how much would it cost?

These small towns are going away because farming technology has undergone extraordinary changes since the 1940s. These changes have allowed food to be produced and sold much more cheaply. In 1901, food was 42.5% of the average US households spending. If we reveres the technological change, we would reverse this reduction in food cost.

We could preserve these smaller towns in some other way, like investing in strong wifi which would allow remote workers to live there while partaking in the cheaper rent and different way of life. The cost would be the cost of wifi infrastructure. The people who paid would be whichever organization, government or otherwise, paid for the installation.

Which communities are worth paying to protect?

As always, I’m not trying to lead you to a right or wrong answer. It’s hard to gauge what is progress and what is loss. It’s natural for it to feel like progress when the efficiency makes our life easier, and natural for it to feel like loss when our way of living is the cost.

I’m typing this on a laptop ‘assembled in China’.

Thank you for reading a heavy one.

Kendall

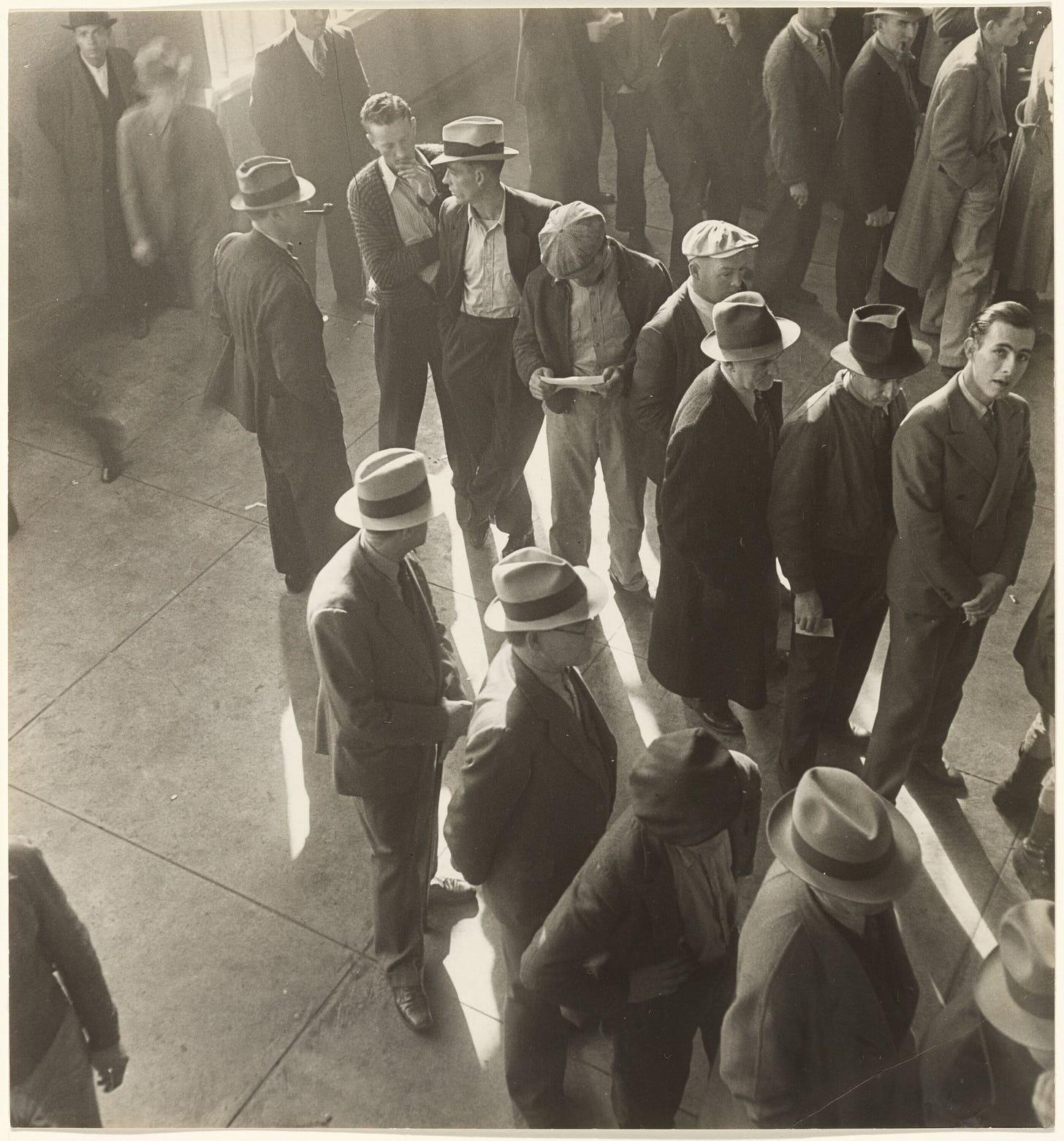

[First Days of Unemployment Compensation in California: Waiting to File Claims]

January 1938

Dorothea Lange